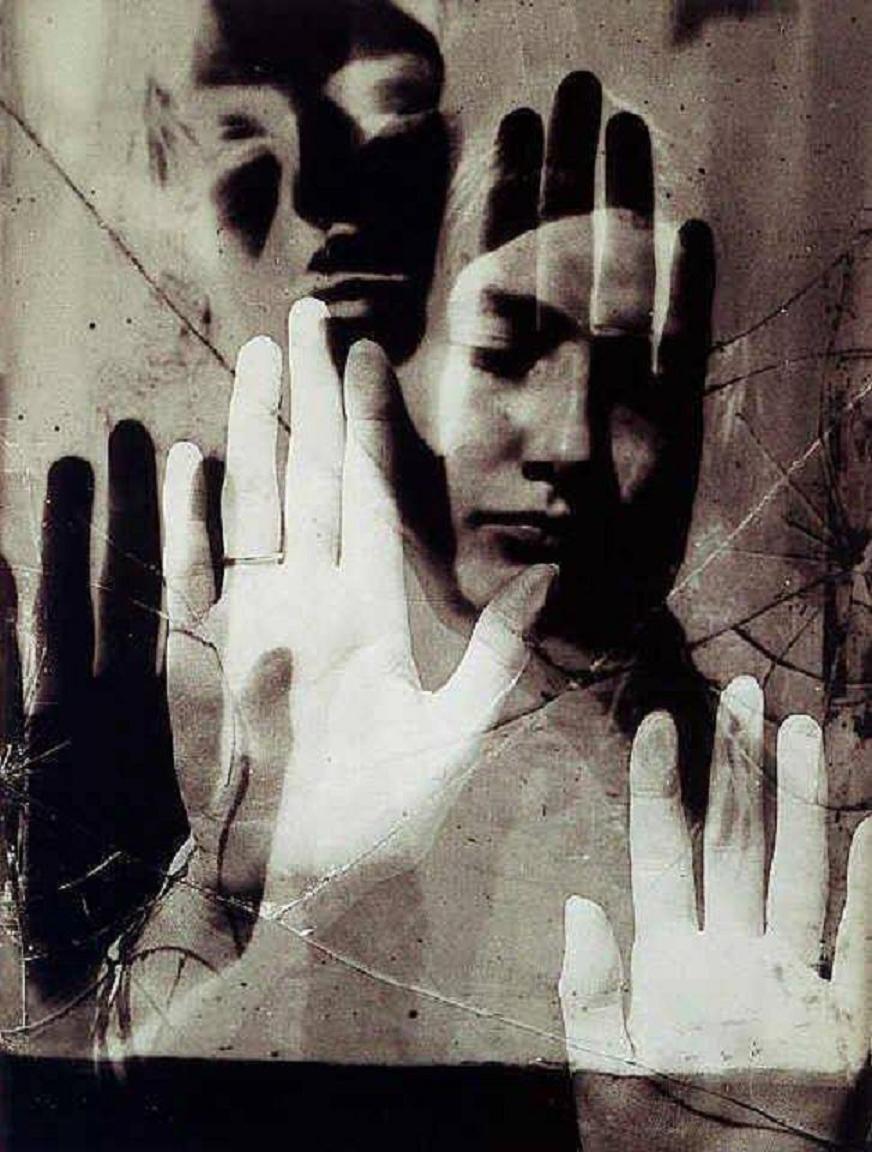

man ray, meret oppenheim, and sexual assault

/Man Ray & Meret Oppenheim, Erotique Voilée (Veiled Erotic), 1933

A few days ago a friend posted this image online with a comment. Her students had noted that 43-year-old Man Ray photographing 19-year-old Meret Oppenheim nude to create this image is "creepy," and I agree. Or at least I think I do.

My first exposure (ha!) to this image was in college, and it startled me then. In a course on the history of photography Ray was an important subject in the first few decades of the 20th century, and some iconic images I didn't associate with Oppenheim were (and remain) what I associate most with Ray – see Le Violon D'Ingres below. In retrospect this is surprising, but Erotique Voilée was the only nude subject in the history of photography textbook that had either nipples or body hair visible, so this registered with me. I was, after all, 18.

Le Violon d'Ingres (Ingres' Violin), 1924

Le Violon d'Ingres is a complex image and, typically for Ray, the title is an important aspect of its complexity. The image is of a nude woman with a turban, on whose back the f-holes of a violin have either been superimposed, painted, or fixed in some way. While there is the visual joke of the woman's body's visual similarity to a violin, it is also a disturbing image: stare long enough at her back and her armless state becomes slightly monstrous, and the tension between her objectification as a nude woman, as a disturbing body resembling an object, and the question of how she has attained this state (did the photographer chop off her arms?) becomes overpowering. The title adds to this, in that it is a French idiom that refers to one's hobby; to describe a nude model as one's Violon d'Ingres is to imply that she is the artist's hobby as Ingres' violin was his. This too is both a joke, playing on the received view of bohemian behavior among such people at the time, and a disturbing way to describe another human being.

But after my friend posted the image and her comment, I was caught. The image stayed in my mind, as good art does, and I chewed on it at the gym, on the bus, walking to work. The revelations about how powerful men treat their coworkers that have increased in frequency in recent weeks have surprised me by their severity and by their ubiquity, and to know that Man Ray was implicated in this widespread, toxic sexism was more a reminder than a newsflash – one I was sorry to get. Ray's work with x-rays and other forms of visual representation, however unsafe they might have been for the subjects or the artist, are arresting, and like the Mad Men producer Matthew Weiner, recently accused of sexual harassment, he seems to have something to say about sexual politics despite not being an exemplar of anti-sexist behavior himself.

Untitled Rayograph, 1922

Dora Maar, 1936

Mannequin on Balcony, ca. 1930

In so many of Ray's images the tension between competing interpretations is the source of meaning, and in so many of his images of women or of bodies that resemble or mimic women's bodies, the tension is between a violent reappropriation of a female body and a critique of that violence through a heightened re-presentation thereof. Ray's formal mastery is clear enough, but his identity as an artist is also caught up in the looking relations he consistently establishes between the looking eye of the artist and female or feminine bodies that often seem both broken-down, lacking of some wholeness or other, and frighteningly excessive. Ray was certainly an artist who represented female bodies repeatedly in his work – there are series of nudes of Oppenheim, of Maar, of the model for Le Violon d'Ingres, Kiki, and many others.

Man Ray and Meret Oppenheim, Untitled, 1933

But in the image that began this train of thought there seems to me to be an added tension not always present in Ray's images, and it comes from the subject, Oppenheim. I may be struck this way by this image because I know and admire Oppenheim's work (more than Ray's, to be perfectly frank), and am thus eager to credit her with any special quality I perceive in any image she is in, but there is more to it than that. The image above shows Oppenheim at an earlier point in the printing press series, contemplating her hand and forearm, which are covered in ink. Her body thus marked is placed in the background of the image and in the foreground the wheel of a printing press is visible, Oppenheim's arm, placed on a sheet of paper, set off against the white background. Her arm's placement there suggests that she may be about to be crushed in the press to make an image and, in fact, this is just what has happened in the creation of the photograph through the process of mechanical reproduction - one of Ray's frequent visual jokes. There is also the usual tension, the suggestion of violence in crushing Oppenheim's arm also a comment on how women are crushed by their stereotypical portrayal which, the image suggests, is driven by the profit motive and creates a repetitive trauma visited upon female bodies.

That this was captured before the image of Oppenheim posed with her arm against her forehead, the ink on her forearm facing the camera, her expression absent and her eyes turned away from the camera that begins this post seems likely. What this means is less clear. I'm tempted to argue that Oppenheim and Ray are collaborators here, her control of the image greater than her usual description as 'muse' would indicate. I imagine Ray and Oppenheim deciding together how the image will turn out, Ray capturing Oppenheim's image as she chooses to pose in one attitude and not another, and this is the special quality I see in Ray's images of Oppenheim. Unlike Le Violon d'Ingres, the images of Dora Maar or of mannequins, Ray's images of Oppenheim hum with an energy that doesn't come from Ray but from his subject-who-is-not-an-object-at-all, whose nude body reveals only her appearance while her averted eyes and thoughtful expression hint at the interiority she keeps for herself.

This reading is confirmed (at least in the sense that biases are so often confirmed) by reference to Oppenheim's own work. Ma Gouvernante (My Governess) from 1936 is a gnomic comment on what Irigaray would call the 'dominant phallic economy,' made so simply and yet with such unforgettable conviction, and her Objet (Object) of 1936 does even more with even less.

Ma Gouvernante (My Governess), 1936

Objet (Object), 1936

Where Ma Gouvernante makes a statement that is fairly overt – the women's shoes trussed up as if for a roast, with the paper crowns usually put on the legs of roast fowl for serving to company on the tips of the heels of the shoes, fairly scream feminist commentary – Objet is a mystery from its title to its purpose to its commentary on existence, and as such became a Surrealist icon immediately upon its exhibition. It was the first artwork by a woman purchased by New York's Museum of Modern Art, but what it means remains ultimately unfixed. I choose to interpret it as a commentary on what must be jettisoned in polite society, particularly for women to participate therein: one's hair, one's mammality and bond with one's own body, one's oddity and inner truth. With Objet the tension is between our expectation of a smooth, hard surface suitable for holding something we wish to consume, and the hair that has grown on the surface, making it uncanny, and more importantly, uncomfortable or unusable. That the object was subsequently renamed by André Breton, and the name (Dejeuner en Fourrure or Luncheon in Fur) contains a reference to Venus in Furs, the novel that gave masochism its name, seems apposite; that the wrong name has continued to be applied to Oppenheim's work is both apposite in the context of the oppression of women here under discussion, and rather sad.

While Oppenheim's objectification and the challenges she faced in claiming and maintaining her artistic vision is both uncomfortable to contemplate and anger-inducing, her response – the deliberate refusal to make useful or particularly soothing objects that are nevertheless curiously unforgettable – is part of Oppenheim's artistic vision from her work in jewelry in Paris, for Schiaparrelli, to her Table with Bird's Legs (1973) and even her return to Ray's rayographs, in X-Rays of My Skull (1964). This supports my reading of Oppenheim's important role in the images Ray made of her in the printing press series, but in my research I found a film the pair made, Poison (1934) that seems to confirm that Oppenheim and Ray were collaborators, not artist and model. One wonders who suggested the ending.

Fur Bracelet, 1936

Table With Bird's Feet, 1973

X-Rays of My Skull, 1964

So is the image with which I begin this post "creepy"? Yes, and it is meant to be so, and it may even be creepier than Ray realized. The smear of ink on Oppenheim's arm is evocative of her marked refusal to display her nude body or her status as 'muse' in an ideal, stereotypical fashion, but Ray nevertheless depicts her as such, or tries to. This, and the spate of famous sex monsters stalking the halls of power that are finally getting their justly negative attention, brought low by a resurgence of feminism itself touched off by the most major, signal failure of feminist politics in a generation – the defeat of the first female candidate for President nominated by a major party, who happened to be head-and-shoulders more qualified to run and to govern than the male opponent she lost to – is the kind of complexity that Ray and Oppenheim's art forces us to think about.